Conjurings

A number of prints in this exhibition centre around some rather intriguing conjurings that need a little contextualisation. The story of “Leda and the Swan” represented in Sidney Nolan’s lithograph from the Leda Suite (1961) illustrates a tale from ancient Greek mythology, where Zeus, the father of the Olympian Gods, took the form of a swan in order to seduce Leda, the daughter of King Thestius. After Leda had been raped by the Swan, she returned to lay with her husband Tyndareus that same night. Leda then birthed four eggs out of which hatched her children: the twins Castor and Pollux and the half-sisters Helen and Clytemnestra.

Sidney Nolan Leda and the Swan (from The Leda Suite) 1961, lithograph, 42.2 x 55.3cm. Newcastle Art Gallery Collection.© The Trustees of the Sidney Nolan Trust/Bridgeman Images

Although Leda’s mythical birthing to swan eggs is a curious tale, it turns out that real life can be stranger than fiction. This is especially evident with the Spiritualist conjurings in the early twentieth century, when mediums such as Eva C. and Kathleen Goligher procured a substance called ‘ectoplasm’ while in trance-like states. This ectoplasm was actually rolls of cheesecloth extracted from bodily cavities and hurled around candlelit rooms. Yet, the women’s illusionary handling of the material, along with the magical way it was photographed, hoodwinked authorities into believing ectoplasm was real manifestations of spirit entities.[1]

My recent monoprint series ‘Drapery’ (2019) summons the haunting imagery of Spiritualism in a contemporary variation by using ink-soaked cheesecloth as the matrix to create ghostly materialisations. The resulting veils also resonate with the loosely woven death-net cast over two lovers (soon-to-be spirits) in Johann Schellenberg’s eighteen-century etching in the exhibition.

[1] Mary Roach, Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2005), 106.

Considering authorities were deceived by the ectoplasmic conjurings of the twentieth century, it is not hard to imagine how bewildered people felt over the copious rabbit births by the servant woman Mary Toft in 1762. This confusion and controversy was adroitly captured in Hogarth’s etching Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism (1762) through the crowd’s riotous and fainting reactions to rabbits bounding out from Mary’s skirt in the middle of a Methodist church service.

Hogarth took some creative liberties in his representation of Mary’s rabbit births, as she was never in a church service and the rabbits she procured were dead and stored in a hidden dress pocket she accessed surreptitiously and inserted into herself. When Mary’s ploy was eventually derailed by the Royal physician Sir Richard Manningham, the public mocked the medical profession for quackery. The ridiculing was so severe that Mary’s sentence was dropped to try and limit prolonged satire (which failed, thanks to Hogarth). The complex themes these prints engage with, simultaneously eliciting emotions such as repulsion, intrigue and amusement, should not be detached from the violence mythologised against Leda or the real trauma experienced by Mary Toft. [1]

(Ali Bezer Aug. 2019)

[1] Leda's rape by Zeus (the swan version), and Mary’s real miscarriage to her first child in August 1726, prior to the rabbit events.

Ernst Ludwig Riepenhausen after William Hogarth Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism, 1762 1820, engraving, 44 x 35.5cm. Private collection.

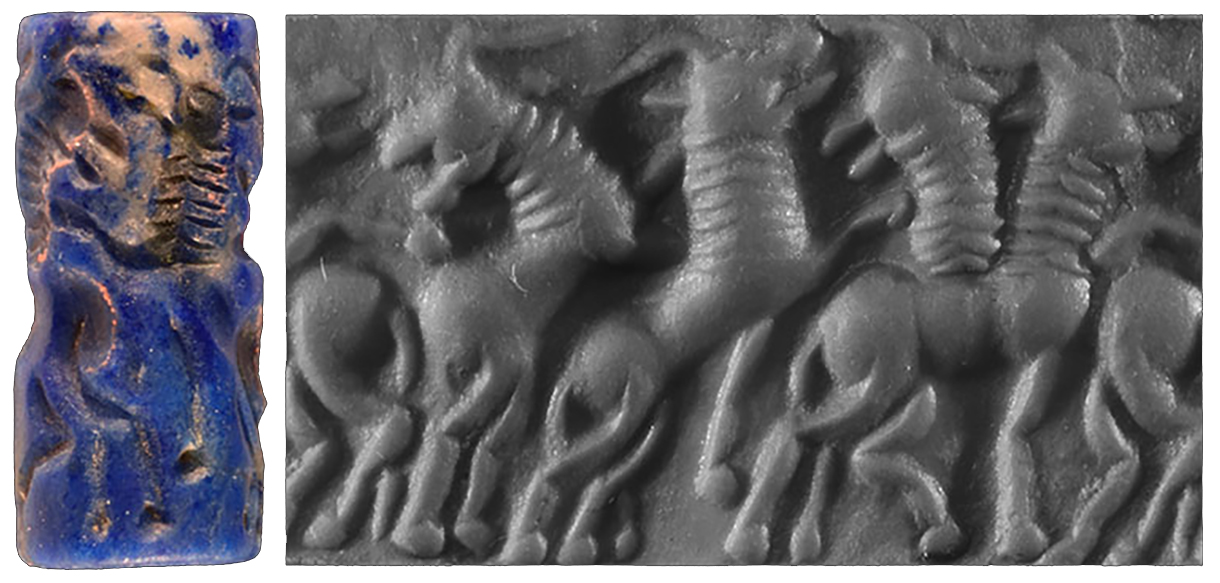

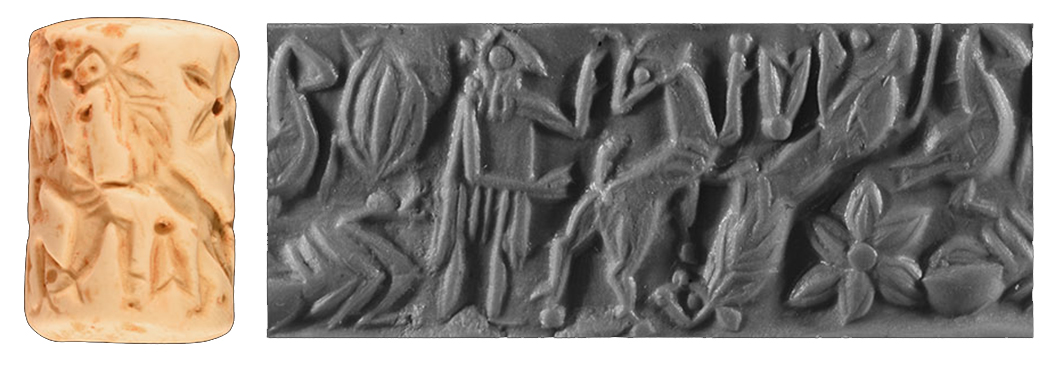

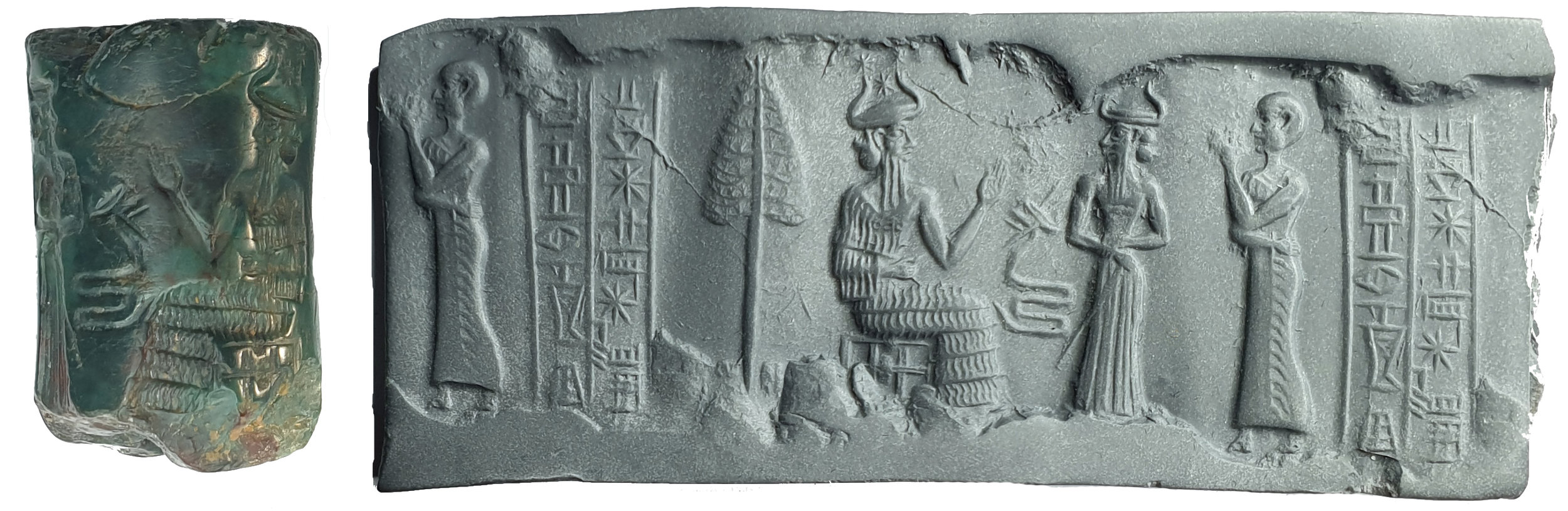

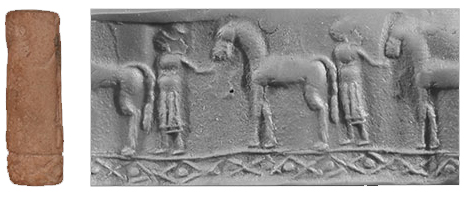

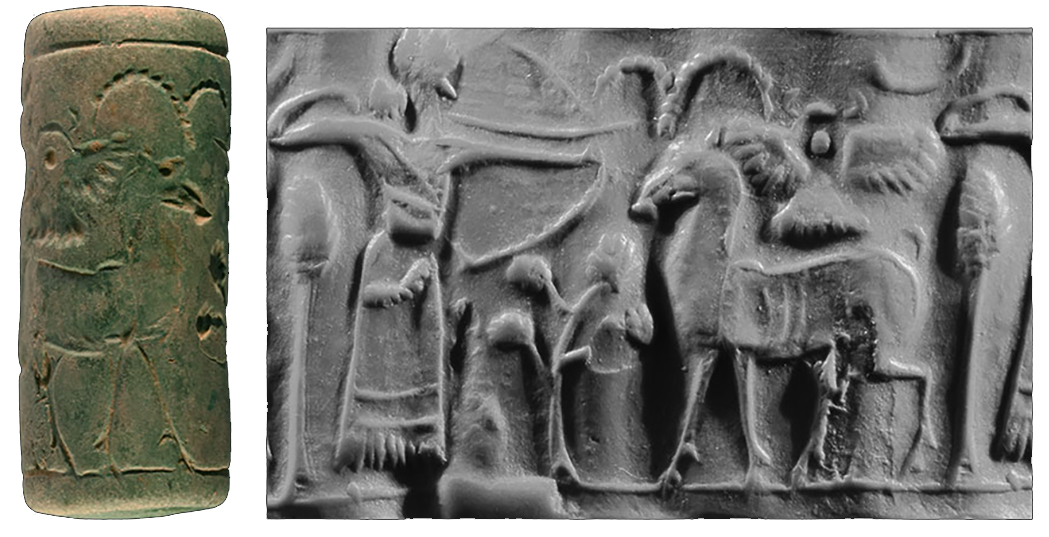

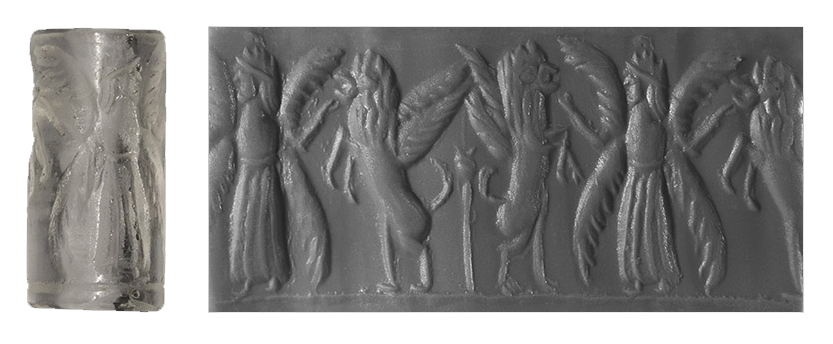

CYLINDER SEALS

Cylinder seals were found in and around the region of Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East which included Assyria and Babylonia and the cities of Nineveh, Nimrud, Babylon and Ur.

The most accessible, yet authoritative books on cylinder seals are by Dominique Collon an archaeologist who worked at the British Museum off and on from 1964 – 2005. Her most recent publication is: First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East London: British Museum Pub., London 1987; new edition 2005.

The following cylinder seals represent a selection from the exhibition and are arranged here to show the stylistic development of the designs across three thousand years. All of these seals from a private collection were acquired through accredited auctions in London and many were authenticated by W. G. Lambert (1926–2011), Professor of Assyriology at the University of Birmingham, 1970-1993. The one early Syrian object was cleared by DFAT in Dec 2017 for import into Australia.

The majority of the cylinder seals produced in the three millennia BCE have the following characteristics in common. Cylinder seals come in various sized within the range that can be held between two fingers, but, as the name suggests, the basic shape is a cylinder and designs are carved or incised on very hard, usually precious or semi-precious stones, sometimes with natural complex patterning that confuses any visual examination of their fine carved detail. They are almost always drilled mostly through the centre, to be worn around the neck or attached to clothing. From cuneiform inscriptions we know they were owned and worn by all levels of society. For the third millennium BCE at least the fineness of the detail must have been carved without the use of a lens, and since there is no evidence lenses were invented until well after that time it has been suggested the artists that made them were myopic, with further speculation that the profession of artist may have been maintained through family lineage, since myopia or near-sightedness is a hereditary condition. Without access to any advanced metallurgy, the drilling of the fine holes and engraving of detail in the early seals must have involved flint drills, spun with thin twine. Because of their ubiquity and durability, thousands have survived but no actual record as to how they were manufactured appears on the surviving countless clay cuneiform tablets. In absolute contradiction to the number of seals, only a handful of contemporary seal impressions have survived, the clearest evidence that they were used to stamp wax and air-dried clay seals over hessian sacking or timber containers and therefore broken on opening.

For an illustrated version of the above see Artemis Vol 51, No 1 Feb. - June 2020.

The huge collection of Cylinder seals from the Ancient near East in the British Museum is accessible online: British Museum.

Copyright © All rights reserved