EMBLEMS

Initially intended as a holiday amusement to be circulated among erudite friends, the original Emblemata (1522) was an unillustrated manuscript based on antiquarian motifs, invented by the academic lawyer Andrea Alciato. The emblems consisted of puns, witticisms, and morals and were influenced by undeciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, thought to contain mystic wisdom. In the first printed edition of the Emblemata, the presentation had evolved into a tripartite form which aligned with the formats of popular illustrated fables, proverbs, or bestiaries, made up of a motto, an illustration, and an epigram. However, they might also consist of only one or two of these elements.

The Emblemata prints were often produced by artists unable to read Latin, which meant that misunderstandings and errors regularly appeared in them. These incongruous additions resulted in a combination of learned and folk motifs, so that emblematic forms mingled sources inventively. Meanings shifted according to the preoccupations of the times, but there always remained a moral dimension concerned with human failings and virtues. Throughout the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the use of emblems became embedded in all aspects of culture, as they were constantly adapted to suit new purposes and contexts.1

Three plates in this exhibition are from Johann Theodor de Bry’s Emblemata Secularia (1596). This suite of emblems reflects the life and manners of the times, reworking images from artists such as Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Consequently, many of the illustrations possess a hallucinatory strangeness.

One depicts a scrum of women fighting over a man, with squads of soldiers in pike squares appearing in the background, alluding to the war against Spain that had caused the acute shortage of men. The emblem has a general application to an amusing sexual role reversal, as well as to a specific social situation (see also R - Risky Relationships).

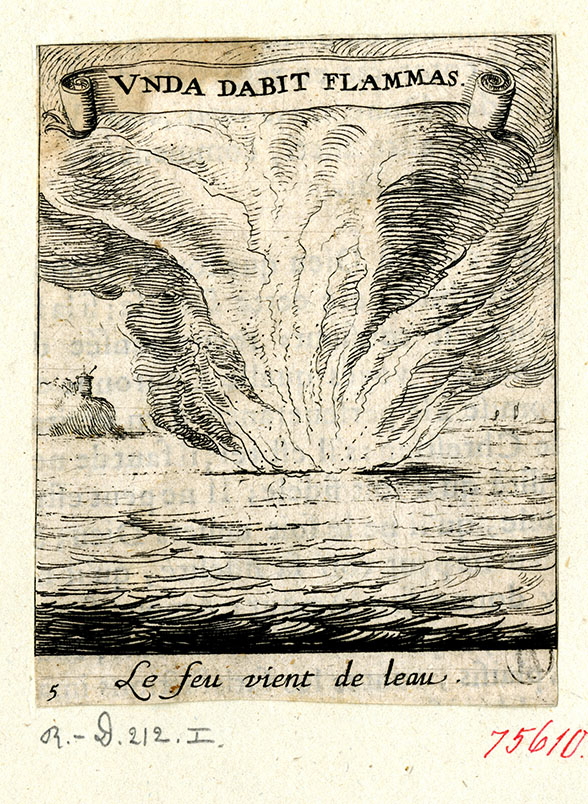

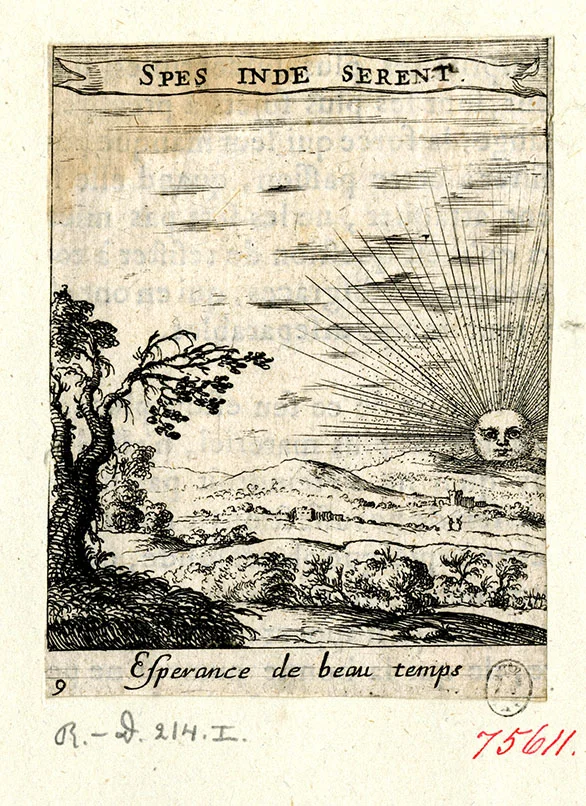

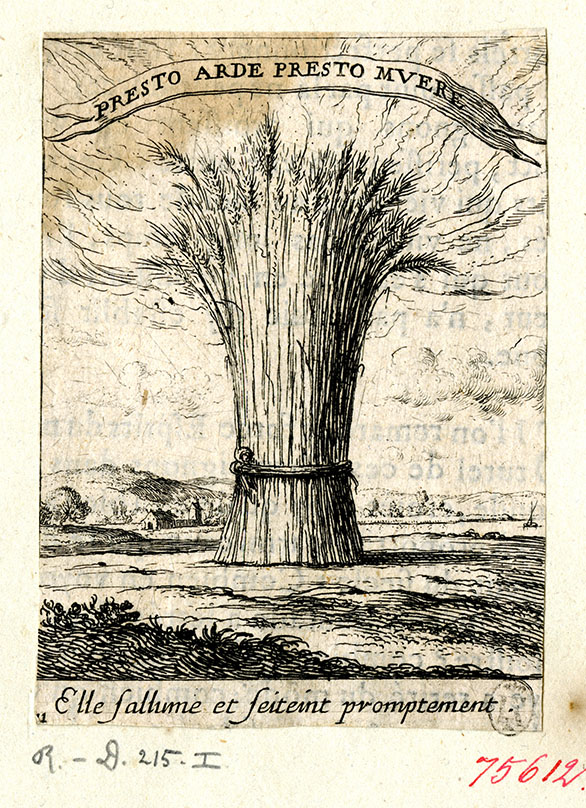

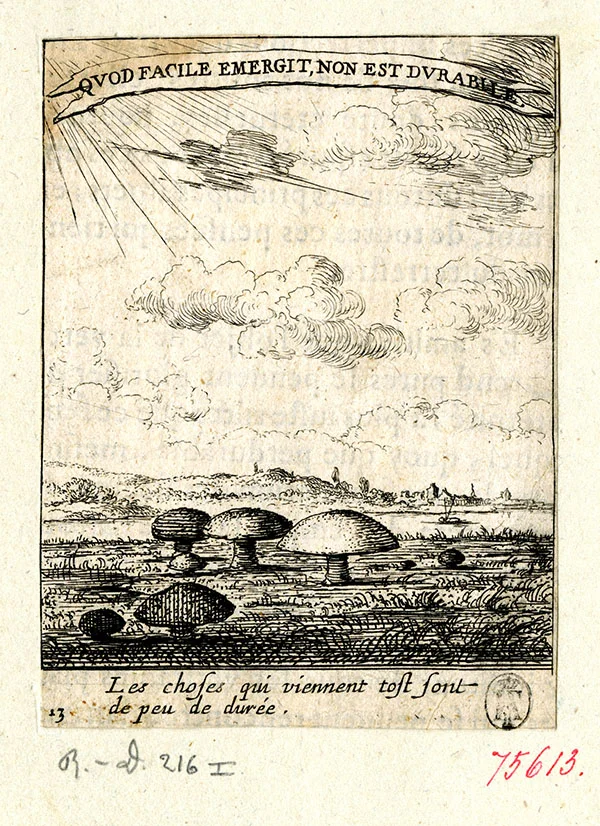

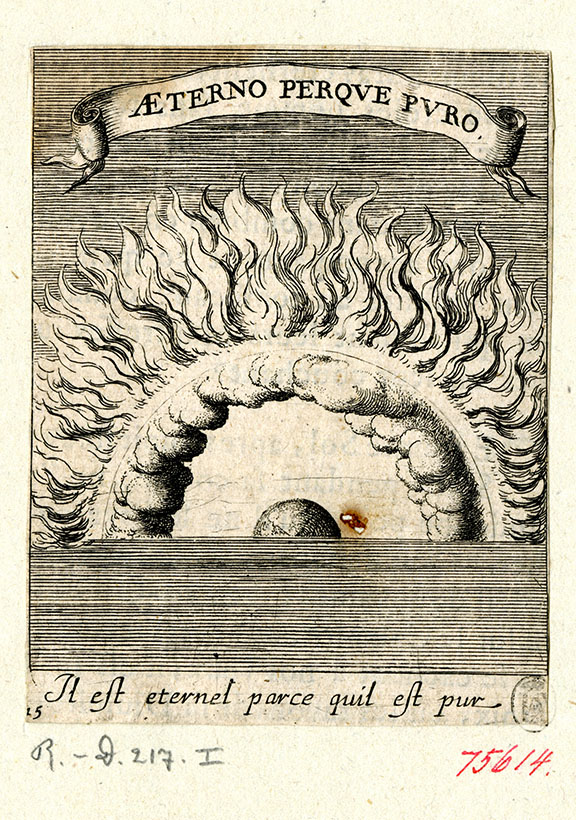

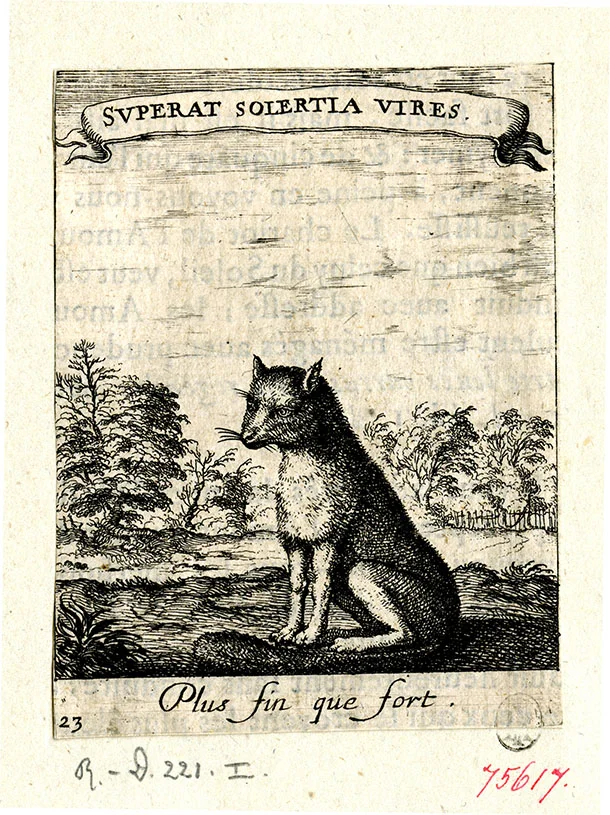

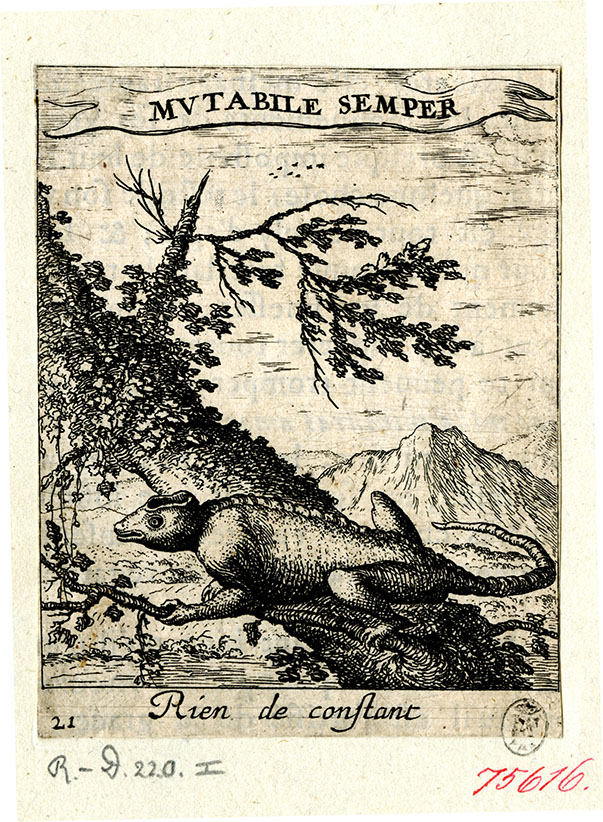

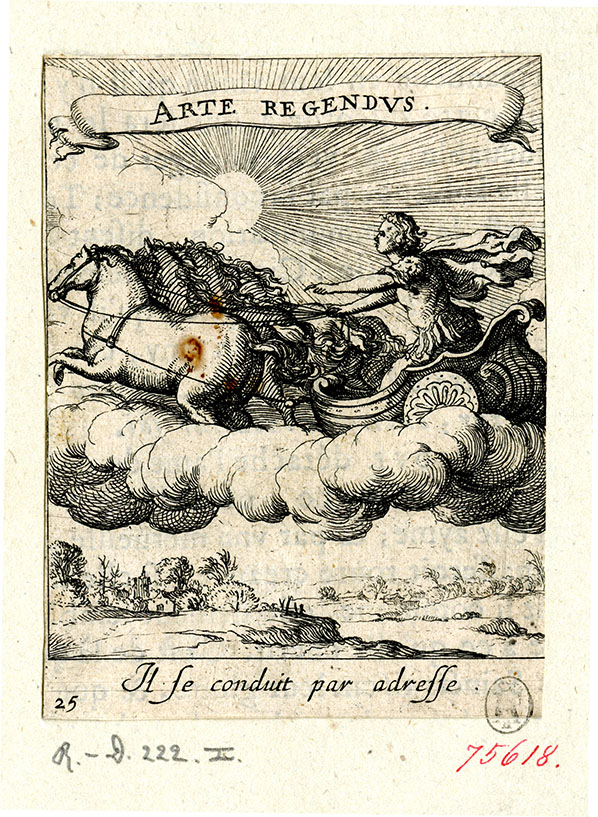

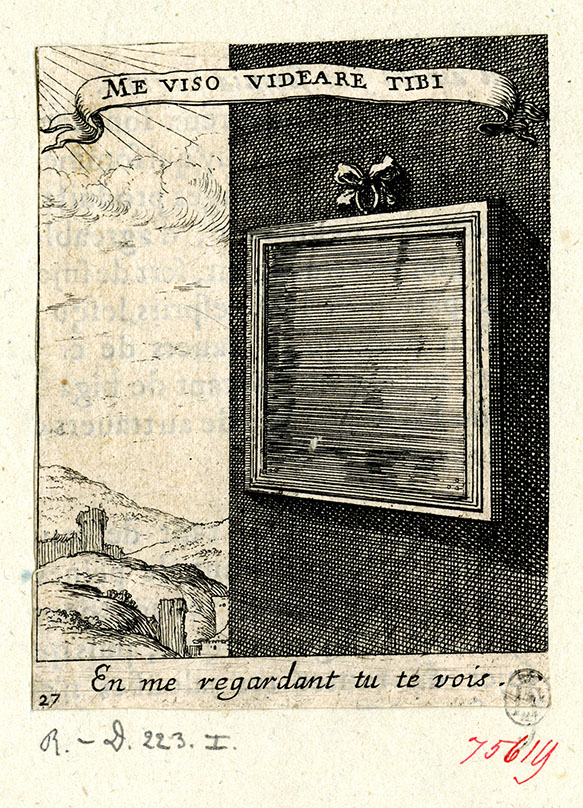

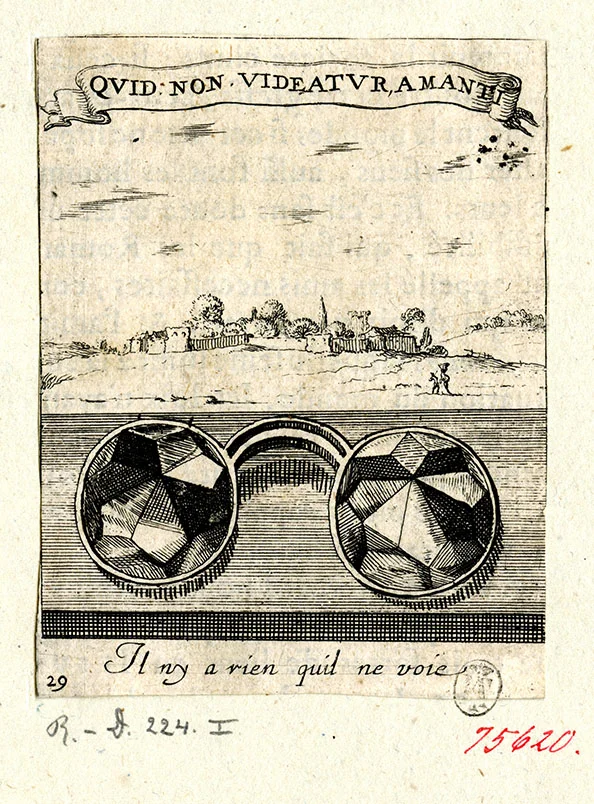

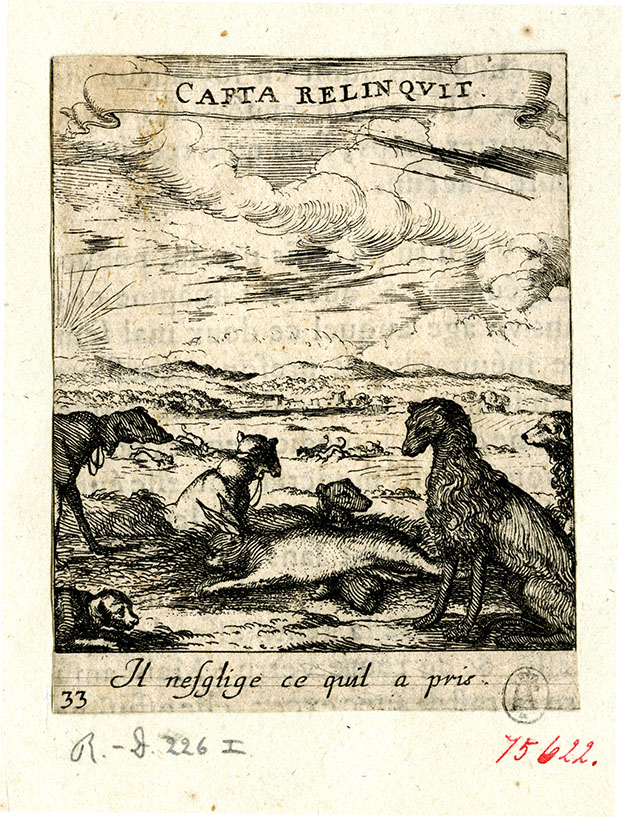

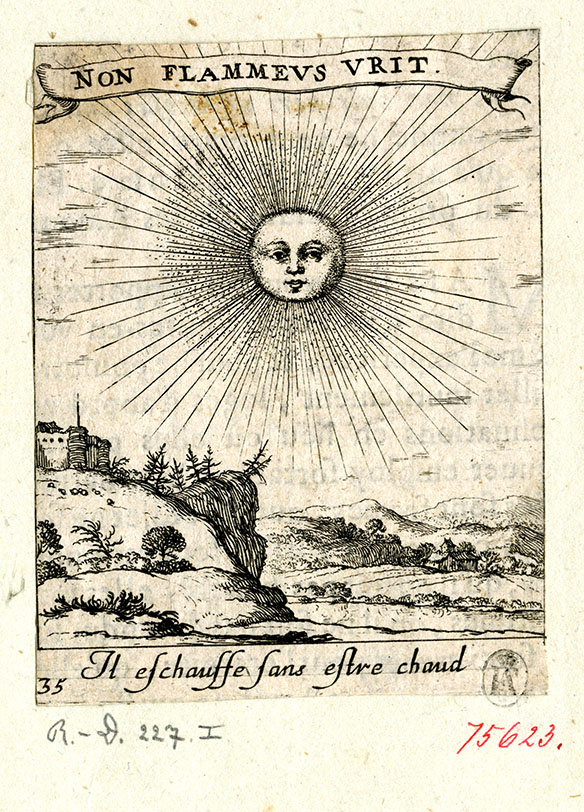

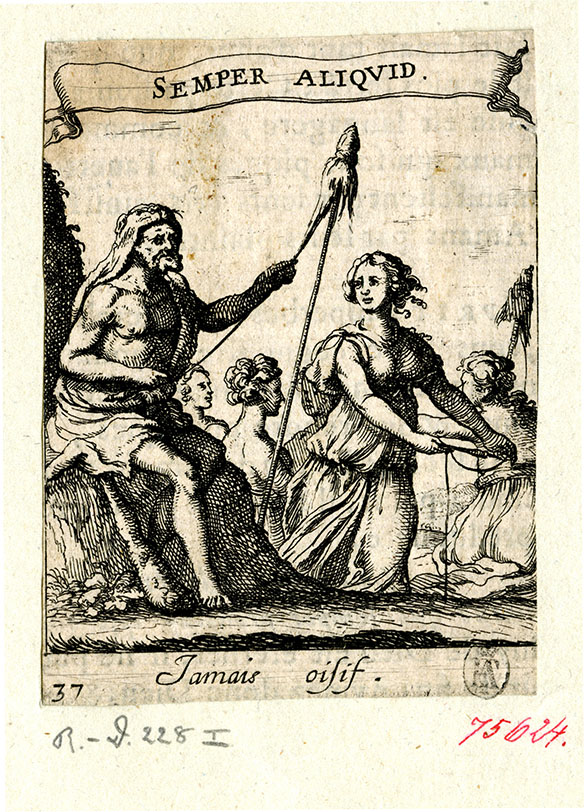

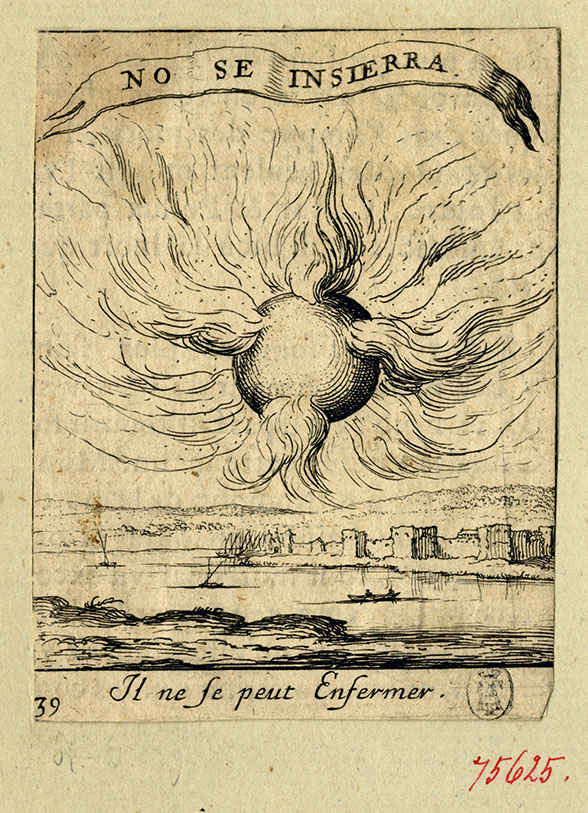

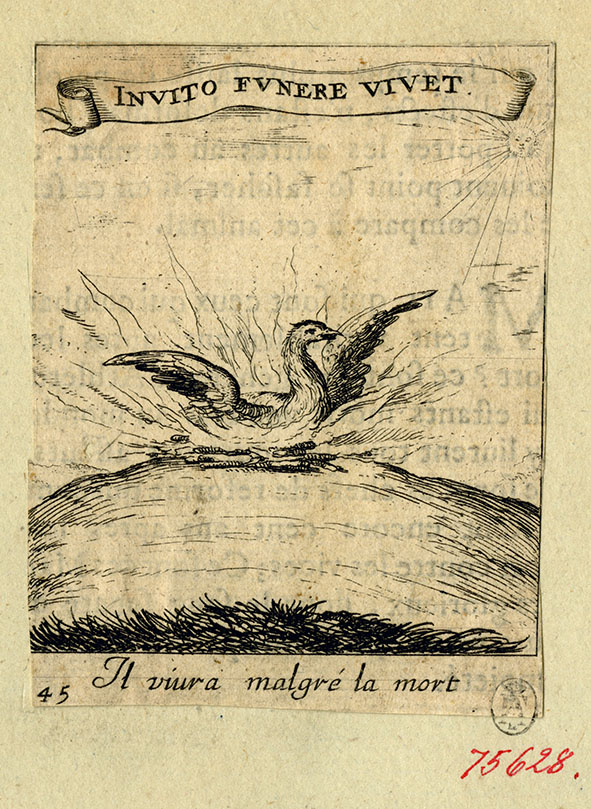

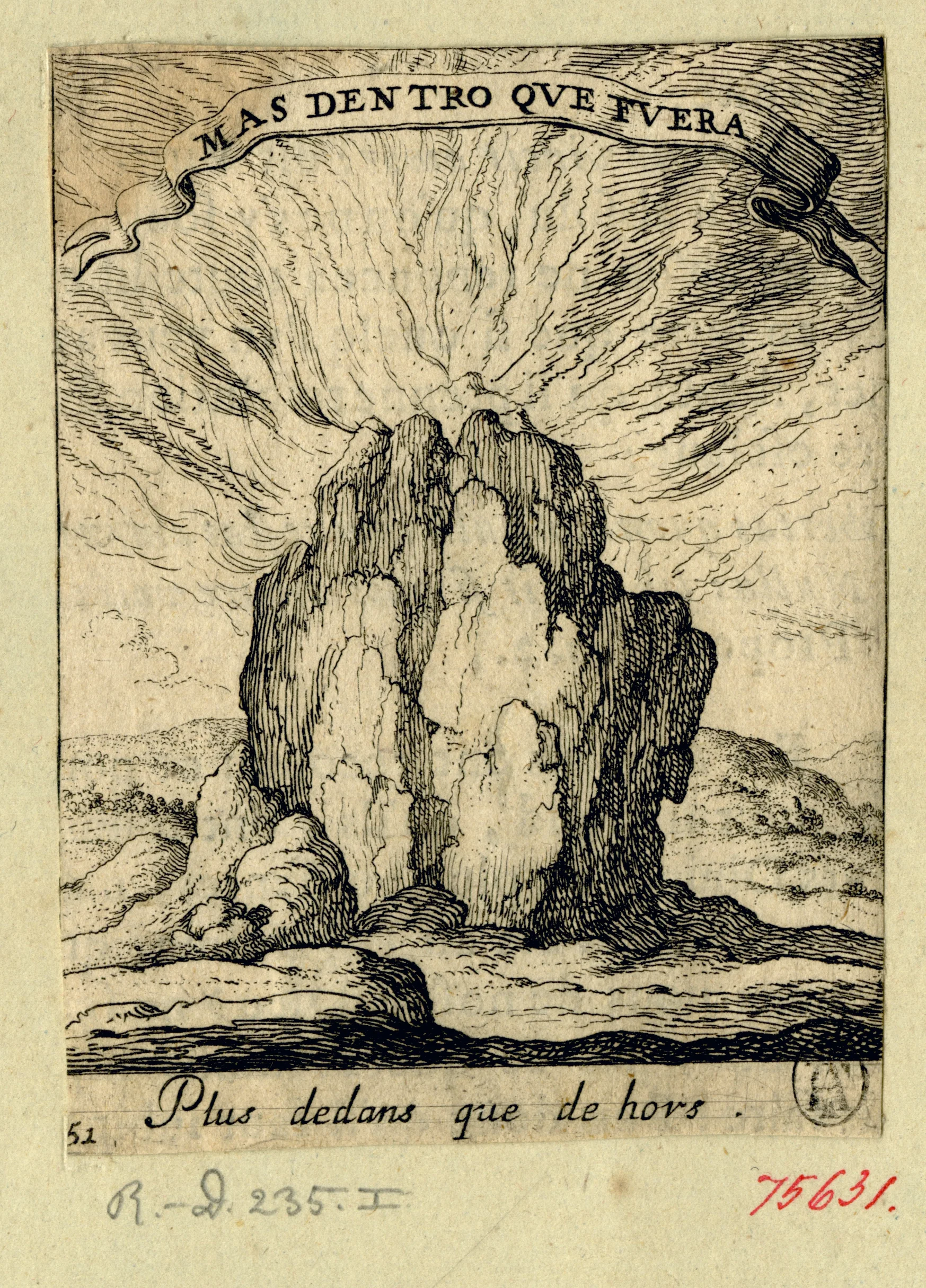

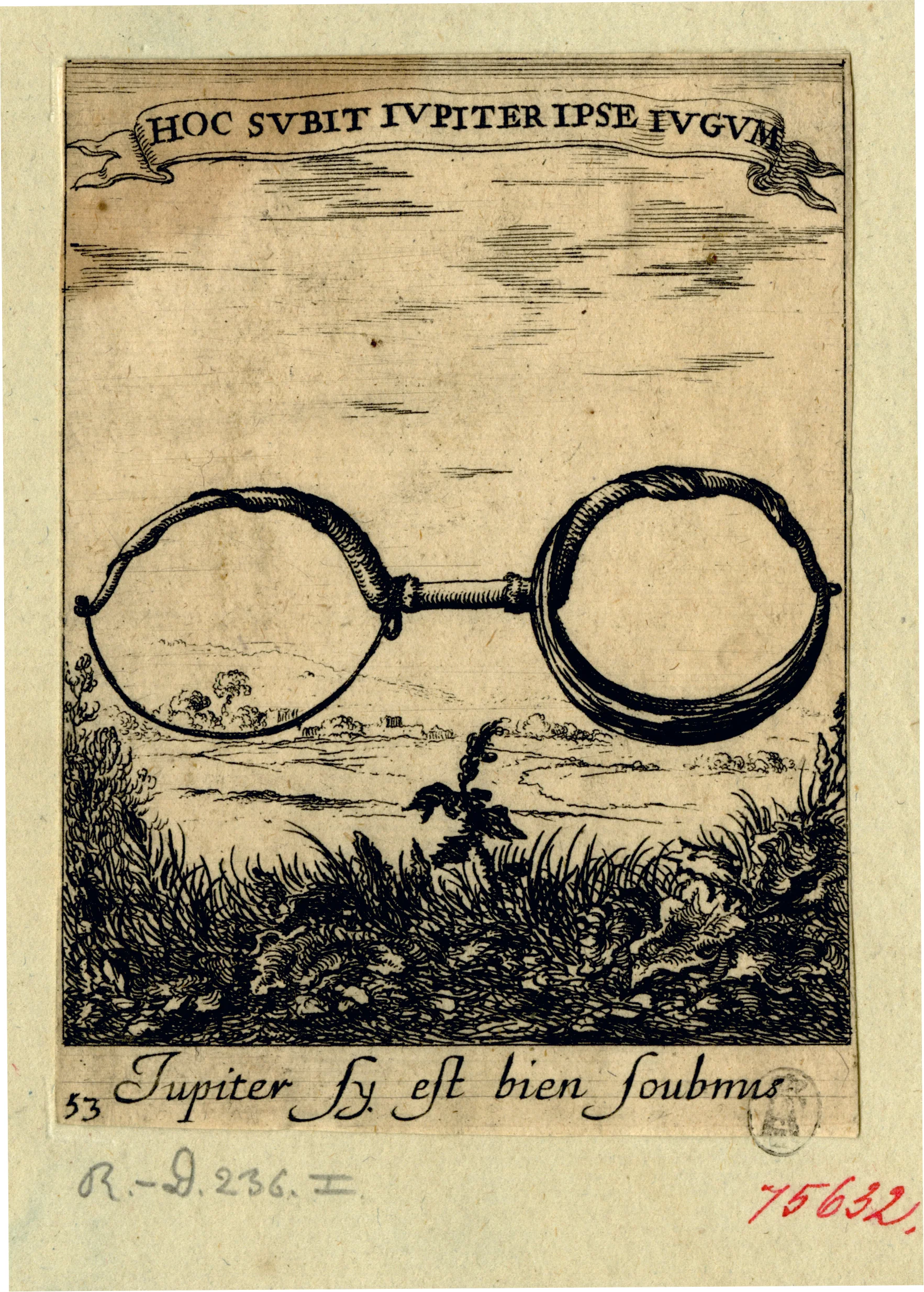

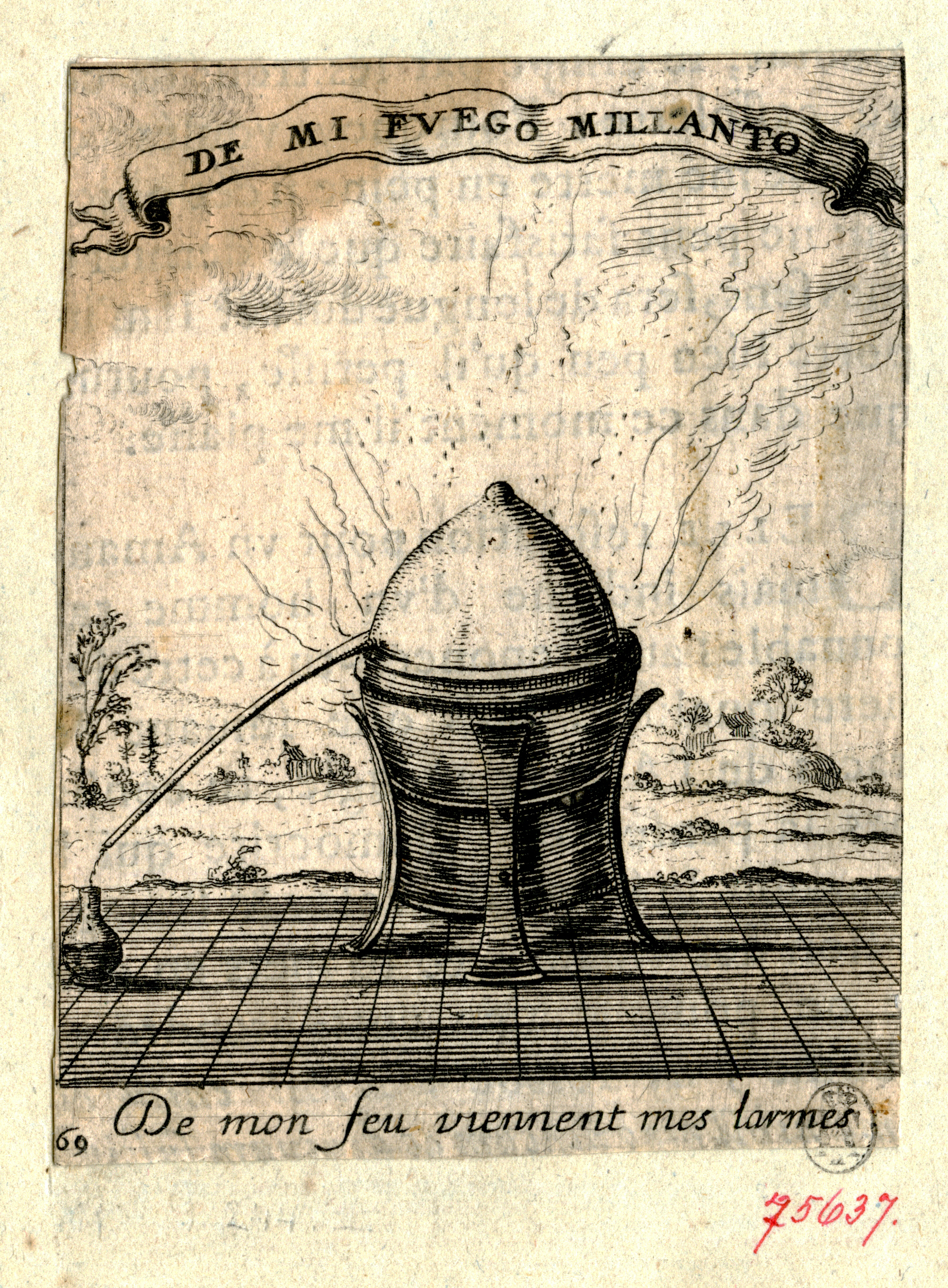

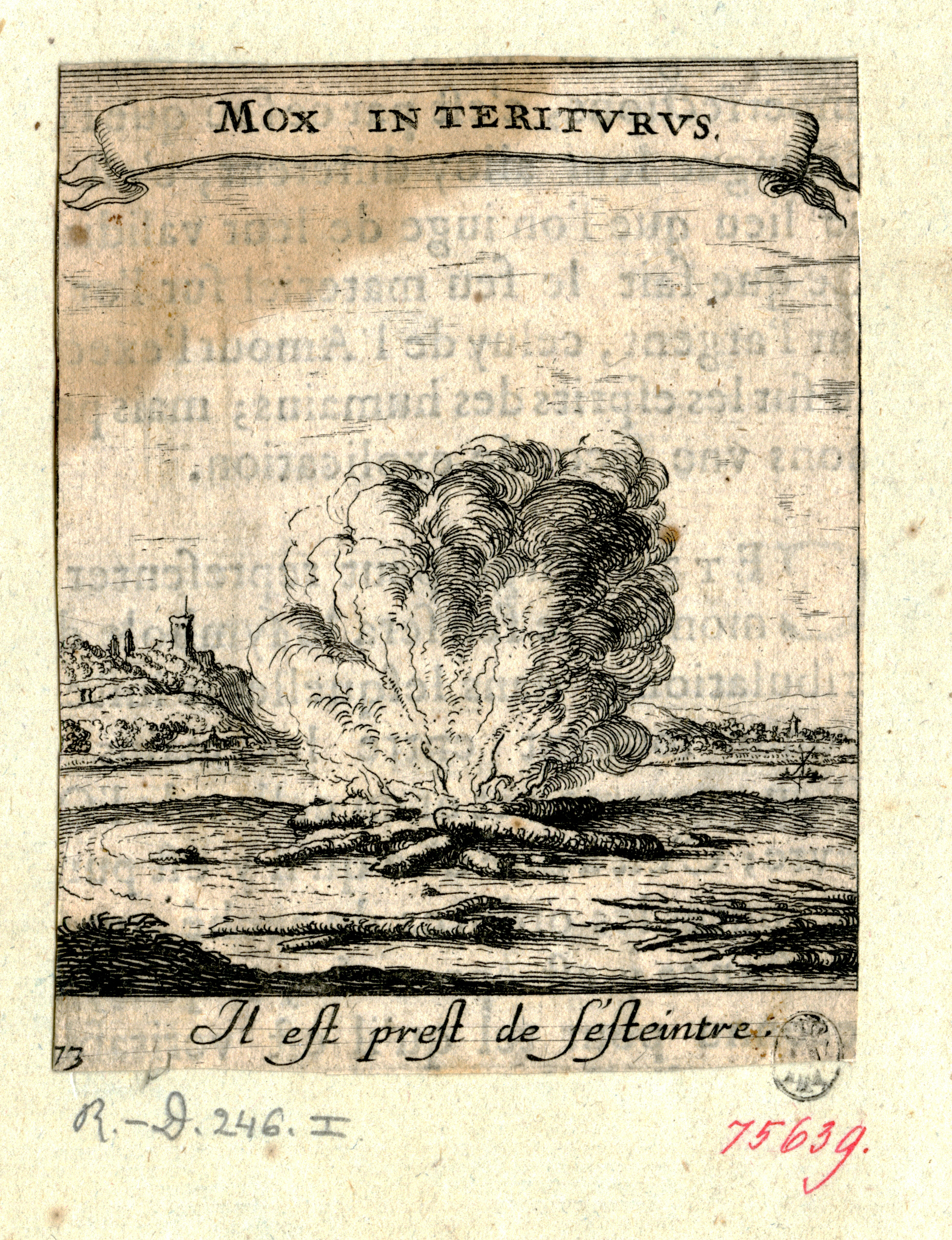

The sheets from Albert Flamen’s Devises et Emblesmes d’Amour (below) show the illustrations with their mottos in Latin and French, which were accompanied in the book by commentaries. This emblem book, first published in 1648, was very popular and was produced with

variations in several editions over twenty-five years.2 Plate 21 depicts a moody chameleon. The Latin motto reads “always changeable”, while the French motto reads “never constant”. The mottos are explained as referring to the fickleness of women, and as a generalised hypocrisy. Many of the plates depict variations of sunlight and flames to represent love’s passion. Plate 75 shows a pot heated in a smoky fire with the motto “valid and proved”, referring to love as a test of the quality of human character and life as a trial to prove Christian faithfulness.

Albert Flamen (1620 – after 1669) selection of engravings from Devises et emblesmes d'amour, 1653.

Emblem books were published in Spain into the late eighteenth century, so the emblematic tradition can be linked with the format of Francisco Goya’s print series. A drawing of his is captioned with a verse from Otto Vaenius’s Emblemata Horatiana (c. 1607) and although Goya’s prints have a darker mood, the emblematic style is reflected in the symbolism, social comment and satire that appears in Los Caprichos of 1797–99.3 These prints ridicule social and religious hierarchies and conventions, reinforced with ironic and often ambiguous captions. Plate 72, No te escaparás [You will not escape], depicts a flighty young woman menaced by a group of grotesque winged creatures, companions of witches, demons, and evil-doers. Even the innocence of youth will not provide protection from superstition, or dark, predatory influences. Andre Breton, the founder of the Surrealist movement, acknowledged Renaissance painters such as Bosch and Arcimboldo as precursors; they also influenced the allegorical imagery in emblem books. The Surrealists sought to reinstate magical thinking and dream images, contradicting the Enlightenment belief in rationality, a belief that Goya attempted to promote with his prints. The fascination for eccentric, free-associated imagery endures over time, though its intent may mutate, and even reverse.

(Anne Taylor Aug. 2019)

1 The source used for these first two paragraphs is John Manning, The Emblem (London: Reaktion Books, 2002).

2 Allison Saunders, The Seventeenth Century French Emblem: A Study in Diversity (Geneva: Libraire Drosz, 2000).

3 The etchings were produced between 1797 and 1798, but published as a complete album in 1799. Nigel Glendinning, “Goya and Van Veen: An Emblematic Source for Some of Goya’s Late Drawings,” The Burlington Magazine 199, no. 893 (August 1977), 566–71.

Several editions of Albert Flamen’s emblem book are available at Archive.org - including the later, 1672, edition: Devises et emblesmes d'amour moralisez from the Duke University Library.

The most comprehensive resources on the Web for information on the EMBLEM are the Glasgow University Emblem Website

This link is to a late variation of the Emblem book as collection of moral tales for educating the young. This example has thirty wood engravings by Thomas Bewick’s younger brother John. Text by: John Huddlestone Wynne (1743-1788) Wood engravings by: John Bewick (1760-1795) Tales for youth: in thirty poems : to which are annexed, historical remarks and moral applications in prose. Printed by J. Crowder for E. Newbery, the corner of St. Paul's Church-yard, London. 1794

Copyright © All rights reserved

![Francisco Goya Capricos No. 72, No te escaparás [You will not escape] 1799, etching, 21 x 14.5cm. Private collection.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1569480662001-5X43G6Q8XG34RGWB6K9J/Goya1-300dpiLow+Res.jpg)

![Francisco Goya Caprichos No. 20 Ya van desplumados [There they go plucked] 1799, etching, burnished aquatint and drypoint on laid paper, c. 21 x 15cm. Private collection](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1569480657758-ZKV0LV0KRQE8W2I9EIPY/Goya2b-300dpi.jpg)