GENOME

For thousands of years, people have attempted to understand the interconnectedness of life on Earth. The comparisons of humans and animals (as seen in Lavater’s Frog to Apollo and Pieter Camper’s Ape to Apollo illustrations) were important missteps on the path towards accurately describing evolution and locating the method by which life stores the information needed to reproduce.

The hand of the artist has always been subject to unconscious mental prejudice, but even the mechanically produced image such as the photograph is not immune to preconceptions and misreading.

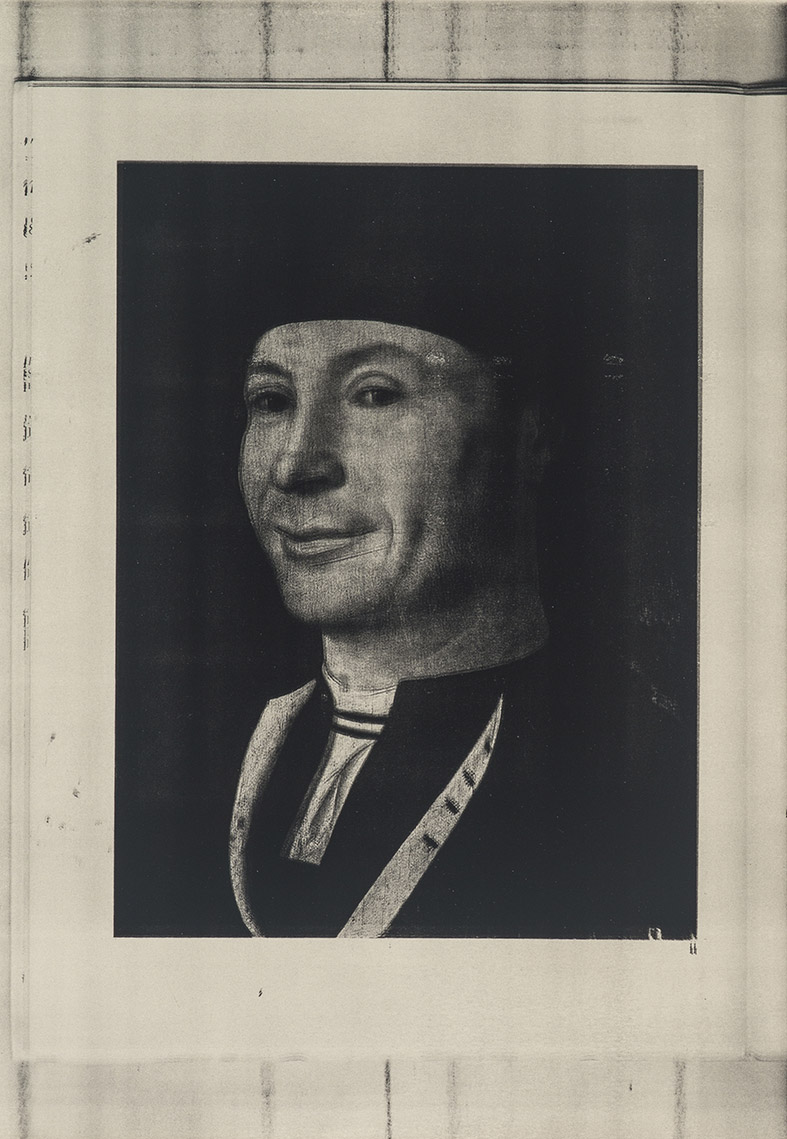

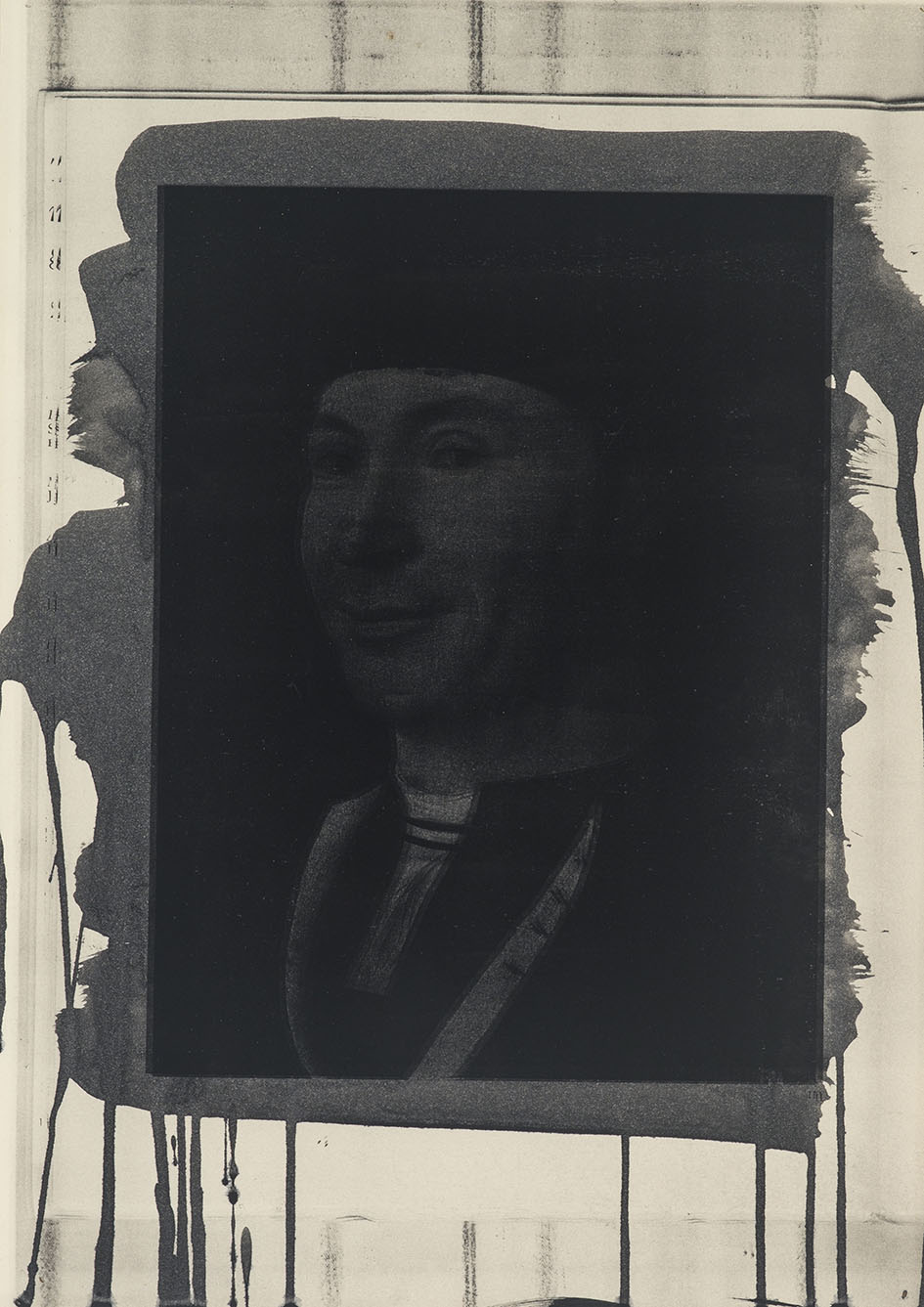

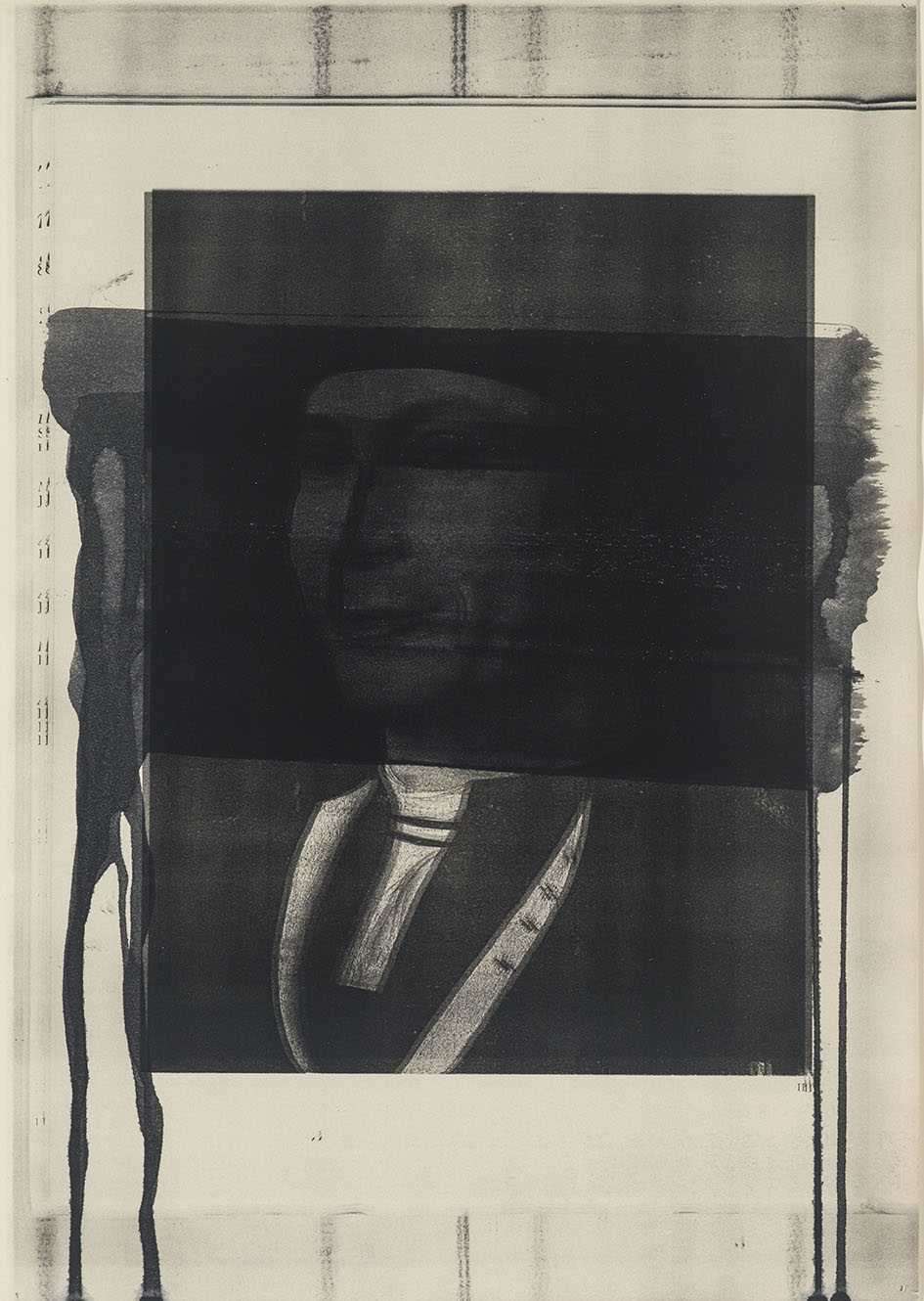

Lindy Lee’s three-part work Untitled (1987) utilises a photocopy and acrylic paint to explore the imperfection of the mechanical reproduction and its relationship to the portrayal of identity. The image exposes the self-portrait of a Renaissance painter to the degradations of successive layers of photocopying and repainting.

Speaking about this body of work that references her own Chinese-Australian cultural identity, Lee states: “I loved the flawed copy, because it was a representation of what I was; I felt split and divided, and it was supremely painful.”[1]

[1] Lindy Lee cited in The University of Queensland, "UQ Art Museum Showcases 30 Years of Lindy Lee," The University of Queensland, https://www.uq.edu.au/news/article/2014/09/uq-art-museum-showcases-30-years-of-lindy-lee.Thomas Kirk engraver, Ape to Apollo TAB I, in Petrus Camper, The Works of the Late Professor Camper, on the Connexion between the Science of Anatomy and the Arts of Drawing, Painting, Statuary, etc., trans. T. Cogan (London: Dilly, 1794). Private collection.

Thomas Holloway after drawings by Johann Lavater, Frog to Apollo in Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy, trans. T Holcroft (London: C. Whittingham , 1804). Private collection.

Thomas Kirk engraver, Ape to Apollo TAB I, in Petrus Camper, The Works of the Late Professor Camper, on the Connexion between the Science of Anatomy and the Arts of Drawing, Painting, Statuary, etc., trans. T. Cogan (London: Dilly, 1794). Private collection.

Ernst Haeckel, Plate 51 Polycyttaria, in Kunstformen der Natur [Art Forms in Nature], approx. 28 x 19cm. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig & Wen, 1899-1904. Private collection.

in the prints of Haeckel’s work (plate 51 Polycyttaria, from Kunstformen der Natur), the accurate reproduction of his observations was constantly in danger of being overtaken by his delight in the geometry of their forms and his compositions. (see page xxx)

The search for the interconnection of life using new scientific methods found expression in the Human Genome Project, which announced in 2000 that it had sequenced the first human genome.

In 2015 I had my genome sequenced as part of a PhD research project at the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University. One of the works created during the project, Conquest, assembles a small section of my genome, representing the scientific conquest of the body, with a Roman bust from the era of the first world empire and Eadweard Muybridge’s photography of an elephant walking, the first mechanically objective images of animal movement.

(Dr Blair Coffey Aug. 2019)

Blair Coffey (b.1970) Conquest 2016 Screen-print on insulation foil 135 x 209 cm. Courtesy the artist

G - GILLRAY

James Gillray (English, 1756—1815)

James Gillray Very Slippy Weather hand-coloured engraving 1808. BM

The print by Gillray in the Stopping Time exhibition, Connoisseurs examining a collection of George Morland's, is discussed below. It is interesting to first examine Gillray’s print Very Slippy Weather from 1808 as it not only illustrates Hannah Humphrey’s print shop, showing where and how many of Gillray’s prints were displayed for sale, but also what the British Museum catalogue entry describes as “a grotesquely ugly ragged boy with skates.” This street urchin is of course modelled on one of the earlier numbered creatures in Lavater’s “Frog to Apollo” evolution diagram that had been published four years before Gillray made this print. Gillray was not the only artist to use Lavater’s “Frog to Apollo” transformation as this example by the great French illustrator Granville shows. However it was a short lived flirtation by artists with the frog as the zero point of human evolution.

From Lavater’s Frog to Apollo engraving.

Grandville (Jean Isidore Gerard, 1803 – 46) Illustrations 1843 - 1844

For a full description of the Gillray prints in Humphrey’s window see the British Museum Entry.

James Gillray (1756—1815) Connoisseurs examining a collection of George Morland's, 1807, hand-coloured etching and aquatint : 36 X 26.6 cm. Private collection.

Description {from the British Museum catalogue]:

A corner of a room hung with unframed canvasses is a background for five men, all in profile to the left. Four closely inspect a picture of two vast pigs lying outside a thatched hovel. The foremost, an old man, peers through spectacles held reversed; in his left hand is a 'Catalogue of Pictures by Morl...'. He is identified in the 'Illustrative Description', 1830, and by Grego, as Captain Baillie, the engraver and connoisseur, by Wright and Evans conjecturally as J. J. Angerstein. Behind is a profile identified as that of Mitchell, a banker; next is Caleb Whitefoord, looking through his glass (see BMSats 8169, 8725, &c). Behind him stands George Baker, a patron of English water-colour painters [print collector and bibliophile], holding a paper on which the word 'Pigs' is legible. Standing apart, with a grossly fat nan pressed on a canvas which he raises from the wall, is Mortimer, a picture-dealer and restorer. He puffs and spits from coarse protruding lips a picture, the head and shoulders of an enormous boar. The pictures burlesques of Morland's manner: (1) A grossly fat butcher inspects a fat pig displayed by a farmer; (2) a man with a pitchfork drives pigs from a stackyard; (3) a yokel embraces a haymaker in a barn while a braying donkey looks in at the door; (4) a mounted sportsman at an alehouse door takes a glass from a hugely fat woman; (5) a ragged woman with an infant on her back tells a stolid farmer his fortune. On the floor, in front of the connoisseurs, an empty frame and a bulging portfolio labelled 'Sketches from Nature by G. Morland' lean against the wall. 16 November 1807.

Additional notes for the BM catalogue:According to the biographical note in the catalogue of his sale at Sotheby's on 16-27.vi.1825, George Baker was angered by Gillrays's portrayal of him in this print and it was consequently withdrawn from display in Mrs Humphreys's shop window.(Comment from Jones 1990)

James Gillray (1757-1816), 'Connoisseurs examining a collection of George Morland's'

Gillray's print has a particularly apposite place in any exhibition concerned with forgery, for it both comments on the work of a much-forged genius, and provides us with a striking likeness of a renowned copyist of the Old Masters: George Morland. To understand it we must retrace the career of Morland, an artist who urgently needs the reassessment of a major exhibition. He studied with his father Henry Morland, a portrait painter, and at the Royal Academy Schools, and first exhibited sketches at the Royal Academy in 1773 when he was ten. By the age of seventeen he enjoyed a considerable reputation as a landscape, genre and animal painter, but during the 1790s the expense of his alcoholicism led to him becoming the victim of unscrupulous dealers. He produced a vast number of canvases in his last decade which were taken from him before they were dry (sometimes even before they were finished), touched up by others and sold. Estimates of his total output range as high as 4,000 paintings before his death in October 1804, and the market became glutted with his later slapdash efforts. This is the background to the print which shows, from right to left, Mr Mortimer, Mr Baker, Mr Caleb Whitefoord, Mr Mitchell and Captain William Baillie.

Mr Mortimer was a well-known picture dealer; Mr Baker a friend and patron of Sandby, Herne and other watercolour painters; Mr Whitefoord was a wit, wine merchant and patron of Wilkie; Mr Mitchell was the twenty-four-stone friend of Rowlandson; and Captain William Baillie (1723-1810), a retired Civil Servant and 'copyist'. Baillie, an Irishman who had fought at Culloden, enjoyed a reputation for his copies of Old Master drawings in private collections, and is the subject of one of the impressive preparatory drawings for the print. It shows him peering through his inverted spectacles and is labelled 'A Connoisseur of the Dutch School contemplating a Rembrandt effect'. This is a reference to Baillie's etchings after Rembrandt, and in particular his restoration of that artist's 'Hundred Guilder print'.

James Gillray Connoisseurs examining a collection of George Morland’s

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Captain William Baillie

The degree of preparation required in a caricatural print such as this Gillray, can be indicated by these six surviving preliminary drawings for the print. All courtesy of the V&A collection.

For more on Connoisseurs examining a collection of George Morland’s, the art market in England, along with a Bibliography, see:

Romantic Circles , a refereed scholarly Website devoted to the study of Romantic-period literature and culture. It includes “The Gallery,” a curated collection of Romantic-era images.

G - Goya

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

There are four etchings by Francisco de Goya from the Los Caprichos ("caprices" or "follies”) series in the Logan Art Gallery exhibition. The four shown below are thematically linked in expressing Goya’s mostly negative attitude towards women: Volaverunt, Hasta la muerte, No te escaparás and Ya van desplumados.

The National Gallery of Victoria, in Australia, has a rare first edition of the full 80 plate series titled Los Caprichos. You can read an essay by Frank I. Heckes on how the series came about and why there is so much conjecture about the meaning of the various plates. NGV ART JOURNAL 19 2 July 2014.

Images of the 80 plates are on the Royal Academy Website.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828)

They have flown (Volaverunt.) Plate 61 from 'Los Caprichos'

1797 - 1799. Etching, aquatint, drypoint on heavy laid paper, with watermark Goya wearing a cap (tenth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm. (Private collection)

Volaverunt is one of the iconic images from Los Caprichos and one of the prints that has received the most commentary from art historians. Its attraction is derived from the formal harmony of the image, as well as its influence in the construction of the romantic myth of the artist´s supposed intimate relationship with the Duchess of Alba. In contemporary accounts, the duchess was described as a stunningly beautiful woman, whom the painter portrayed on several occasions, most recently before the publication of Los Caprichos in his portrait of her from 1797, dressed in black and pointing toward the inscription Solo Goya (Only Goya) on the ground before her (Hispanic Society of America, New York). Almost every interpretation of the female figure in this print identifies her with the duchess, explaining the image as a bitter criticism from a spited lover. As is typical of other prints in the series, the Latin title Volaverunt suggests several meanings, for in addition to its literal translation, They have flown, it can also allude to something lost.The hypothesis that Goya is saying that the Duchess of Alba has flown away forever depends on the butterfly wings -a symbol of inconstancy according to a longstanding poetic tradition- emerging from the back of the young woman´s head. But the butterfly may also signify fragility, or that which is ephemeral and changing; it is also conceptually tied to the idea of immortality in the sense of passing on to a new life. Because of its mutable nature, the butterfly is associated with Fortune, and in Cesare Ripa´s Iconologia -an emblem book that provided generations of artists in Europe with their main source of iconographic symbolism after its publication in 1593- the allegorical figure of Imprudence is represented with butterfly wings. In its simplest sense, the butterfly embodies femininity, and since its wings serve to fly, their inclusion in an image of a woman flying seems to be an obvious connection.Tempting though it may be to interpret this print as a commentary on a romance between the duchess and the painter, there is no proof that such a relationship ever existed, nor are there any objectively clear elements in Volaverunt that would allow us to identify the woman as the duchess. A comparison with other female figures in the series suggests a different conclusion. The woman here is wearing the walking dress Goya used for prostitutes in other prints. Significantly, the woman´s legs are spread and her neckline bare. The trio of grotesque characters propelling her flight appear to be witches. Indeed, in the ordering of the prints, this one is included among the scenes of witchcraft. Goya´s witches are a variant of the depraved go-betweens that incite prostitution and lead people to vice. From this standpoint, we may view the young woman in Volaverunt as flitting from man to man as a butterfly between flowers, driven in her flight by the witches (Blas Benito, J.: Portrait of Spain. Masterpieces from the Prado, Queensland Art Gallery-Art Exhibitions Australia, 2012, p. 208). Source: Prado Website.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828)

Until Death (Hasta la muerte.) Plate 55 from 'Los Caprichos'

1799. Etching, aquatint, drypoint on heavy laid paper, with watermark Goya wearing a cap (tenth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm (Private collection)

Widely acknowledged as one of the most important Spanish artists of the Romantic era, Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) was a supremely innovative printmaker, thanks to his experimentation with the newly invented aquatint process. Aquatint produces areas of tone by applying powdered resin to the metal printing plate, and Goya combined this with etching and burnishing to produce images of great tonal depth, employing theatrical contrasts of light and dark.

This is Plate 55 in a series of 80 etchings by Goya called Caprichos. An English sale catalogue of 1814 described Caprichos as representing ‘every kind of vice from the highest to the lowest classes…the avaricious, lascivious, cowards, bullies…prostitutes and hypocrites’. These caricatures, attacking the familiar targets of lawyers, doctors, soldiers and priests, were deeply unpopular with the Spanish Inquisition.

Here an elderly woman admires her reflection in a mirror, as a number of young onlookers suppress their mirth. It represents an age-old topic for social criticism, the deluded vanity of old age, as the wizened crone clings to the illusion of her beauty ‘Until Death’.

Although Goya enjoyed enormous popularity in France, admired by the poet Chales Baudelaire and painters including Édouard Manet, the English were slow to appreciate his work. The critic John Ruskin, disgusted by their ‘immorality’, burned a copy of the Caprichos in 1872, and the National Gallery acquired no works by him until 1896. The antiquarian, Francis Douce (1757–1834) was one of Goya’s few early admirers, owning two copies of the Caprichos. Douce bequeathed his collection of prints to the University of Oxford in 1834 and the majority of these were transferred from the Bodleian Library to the Ashmolean Museum in 1863. Source: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828)

You will not escape (No te escaparás.) Plate 72 from 'Los Caprichos'

1799. Etching, aquatint, laid paper, (eighth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm sheet c. 380 x 270 mm (Private collection)

This plate can be grouped with a number exploring "devils and witchcraft". Goya presents the representation of a young woman persecuted by witches and creatures of the night. The pantomimic gesture of flight can be interpreted as the unconscious search for adventure, or sexual innuendo. Source: Prado Website.

Francisco José de Goya (Spanish, 1746 -1828)

There they go plucked (Ya van desplumados) Plate 20 from 'Los Caprichos'

1799. Etching, aquatint, laid paper, (eighth edition) plate 220 x 150mm. sheet 365 x 260mm sheet c. 380 x 270 mm (Private collection)

This Caprice or Folly is one of a number of plates that relate to prostitution, specifically here the theme of the exploitation of lustful men by unscrupulous women. Goya continues to use the metaphor of men - birds that, attracted by lust, are plucked and stripped of their goods. More than the world of prostitution as such, Goya emphasizes the consequences of prostitution, and emphasizes the foolishness and recklessness of those who neglect and do not gain experience with the misfortune of others. Source: Prado Website.

Copyright © All rights reserved

![Ernst Haeckel, Plate 51 Polycyttaria, in Kunstformen der Natur [Art Forms in Nature], approx. 28 x 19cm. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig & Wen, 1899-1904. Private collection.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1567947962252-DEK0QV8MDVL9BEDCRUDG/Haeckel51WEB.jpg)